For the blog section of the website interviews were gained from creative women. The women selected are independent creatives from a range of artistic backgrounds.

Jasmine Moody

Monday, 30 April 2018

aesthetics

Concept one

- clear minimal layout

- bold and impactive

- block colours, contemporary design trends

- showcase women's work

Concept two

- highly feminine

- elegant typefaces?- is this not feminist

- do the pastel colours make the imagery stand out?

Concept three

- clear minimal layout

- line work-makes imagery stand out?

- is the logo effective in this format?

- two tone colour pallete

- minimal

- modernist layout

- modernism is more a men's movement throught history/postmodernism-women

Thoughts/feedback

- The first design stands out and is highly impactful, although colour should be added as it feels to lack creativity

- The second design is far too feminine and does it express the idea that male and females are equal within the design world.

- As the third design is illustration based it may not be suitable for photography

Wireframes

Initial wireframes were completed in order to gain a better understanding as to how the website may appear aesthetically, as well as its functionings.

Large scale images have been applied in order to showcase female designers work, and outline creative realms.

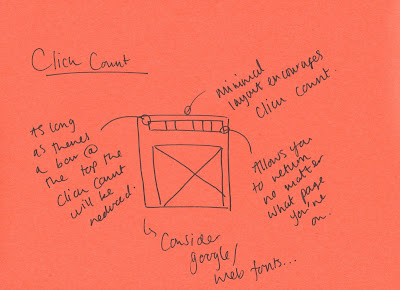

Functionality was widely considered, with links being made between the wireframes showcasing the transitions. These attempt to reduce the click count, further engaging the consumer.

The landing page was discussed in detail in order to gain a better understanding as to a websites effects, and its ease of navigation. It was discussed as to whether the homepage should contain multiple sections or whether it should just act as a transferable link.

It was decided that the landing page would maintain a scrollable section, in turn, instantly engaging the consumer. This also reduces the click count.

Peer feedback

- adding a scroll element is an easy way of navigation

- try to reduce the click count

- add taskbar at the top of each page

Visual Research

Cap gun collective

- easy to navigate

- animated shapes

- bold, clear layout

- typographic approach

Howlt art & design studio

- fun, innovative design

- the style of the website relates to the iconography used

MUI

- minimal layout-makes the imagery stand out

- clear navigational bar

- logo situated on all pages (same place)

Eight Arms

- interactive animated shapes have been used-engages the consumer

- easy to use navigation bar

- logo in top left

- white is clear and simple

Jonathan Patterson

- bold and colourful

- strong imagery

- easy to navigate

- easy to use, different sections evidenced on the hompage.

Tuesday, 24 April 2018

Ideas/feedback

- click count was outlined as a key factor of consideration, with scrolling being included. Peers suggested that scrolling felt less of an effort than clicking.

- It was also suggested that you should be able to reach each page no matter what page you are on.

- mockups may be devised in order to showcase this.

- content for the homepage was outled, including key texts.

- again the home bar was implemented showcasing a variety of options

- The sections of the website were highlighted with a focus being placed upon the homepage, about page, events/workshops section, jobs, how to section, portfolio surgeries and inspiring female creatives formulated into a daily blog.

- extra tabs were also highlighted in order to promote sub-categories

- It was also highlighted that the tab bar will remain the same on each page, with the logo being implemented centrally.

- google/web fonts-cant use all like normal due to coding

- female CEOs as inspiration

- the events lists should not just focus on one city but also rural areas

- upload format for the portfolio surgery

Initial ideas

Following on from the feedback session, small wireframes were developed showcasing the pages of the user interface and how they will work alongside one another.

An initial homepage was outlined, in which will act as the landing page (initially informing the consumer). Then the next movement is the decision of the consumer, with the top icon bar showcasing links to following pages. The bar will remain at the top of each page in order to ensure that the click count is as small as possible, ensuring that the consumer remains engaged.

Creative woman: Akiko Ban, jewellery designer

- DO YOU HAVE CREATIVE HABITS OR RITUALS IN YOUR WORK THAT HELPS YOU STAY FOCUSED AND HAPPY?

Staying fit and healthy is an essential part to stay focused and happy. I do running and take a contemporary dance class. Sometimes I go to Buddhist Centre to do meditation. Listening to nice music and seeing good art and design also make me happy.

- WHAT IS THE MEANING OF 'CREATIVE' TO YOU?

For me, being innovative by making something which nobody has done before. To do that you have to be free and honest with yourself and being unique.

- IF YOU COULD COLLABORATE ON A CREATIVE PROJECT OR IDEA WITH ANYONE... WHO WOULD IT BE & WHY?

It would be amazing if I could collaborate with contemporary dance company because I am interested in the relationship between art and body.

- DO YOU HAVE A FAVORITE PIECE OF EQUIPMENT THAT INSPIRES YOUR DAY TO DAY PROCESS?

Lots of online media especially Instagram and Pinterest.

- WHAT IS THE BEST THING ABOUT WORKING FOR YOURSELF?

FREEDOM!

- WHAT IS THE PROUDEST CREATIVE MOMENT IN YOUR JOURNEY SO FAR?

Our jewelry collection got featured by big museums such as Tate, the British Museum and Fashion and Textile Museum, which was one of my dreams when I started my business. Also our recent collaboration with the high-end Japanese fashion brand ‘matohu’ for their SS2018 collection.

- TELL US ABOUT YOUR BUSINESS

MYSTIC FORMS is a handcrafted jewelry collection by a London-based Japanese artist Akiko Ban, co-directed with a graphic designer Taiyo Nagano.

Akiko is a practicing artist known for her lively drawings and sculptures that seek to establish a primitive, naturalistic and spiritual view of the world. In the process of creating this ‘Wearable Art’, she aims to create a special ritualistic and theatrical art object that acts as a prop and converts the wearer into an art piece themselves.

Akiko holds an MFA in Sculpture from Slade School of Fine Art and a BA in Drawing from Camberwell College. Her works have been exhibited internationally and her recent projects include the collaboration with Basement Jaxx and the high-end Japanese brand ‘matohu’. Her drawing was selected for RA summer show 2016.

- WHAT PART OF BEING A DESIGNER DO YOU PREFER? THE CREATIVE, SALES, SOCIAL OR MARKETING SIDE?

Of course, the creative as I’m an artist! I also enjoy talking with customers and get the direct feedback from them.

- WHAT IDEAS DID YOU TAKE ACTION ON/STEPS YOU TOOK TO GET YOUR BUSINESS UP AND RUNNING?

MYSTIC FORMS started as part of my artistic research project which explores the relationship between art and body. I have chosen jewelry as my medium to demonstrate my belief that art should be more accessible, personal and enjoyable for everyone. I am interested in how people’s perception of themselves changes by wearing my mystic artworks.

- WHAT HAS BEEN THE MOST EFFECTIVE WAY OF BUILDING YOUR TRIBE FOR YOUR BUSINESS AND GETTING NEW CUSTOMERS?

I would say being active on social media and stay connected with your followers and customers. Taking part in trade shows also helped me a lot to get exposure.

- WHAT HAVE BEEN YOUR BIGGEST CHALLENGES SO FAR?

Managing cash flow is always challenging.

Staying fit and healthy is an essential part to stay focused and happy. I do running and take a contemporary dance class. Sometimes I go to Buddhist Centre to do meditation. Listening to nice music and seeing good art and design also make me happy.

- WHAT IS THE MEANING OF 'CREATIVE' TO YOU?

For me, being innovative by making something which nobody has done before. To do that you have to be free and honest with yourself and being unique.

- IF YOU COULD COLLABORATE ON A CREATIVE PROJECT OR IDEA WITH ANYONE... WHO WOULD IT BE & WHY?

It would be amazing if I could collaborate with contemporary dance company because I am interested in the relationship between art and body.

- DO YOU HAVE A FAVORITE PIECE OF EQUIPMENT THAT INSPIRES YOUR DAY TO DAY PROCESS?

Lots of online media especially Instagram and Pinterest.

- WHAT IS THE BEST THING ABOUT WORKING FOR YOURSELF?

FREEDOM!

- WHAT IS THE PROUDEST CREATIVE MOMENT IN YOUR JOURNEY SO FAR?

Our jewelry collection got featured by big museums such as Tate, the British Museum and Fashion and Textile Museum, which was one of my dreams when I started my business. Also our recent collaboration with the high-end Japanese fashion brand ‘matohu’ for their SS2018 collection.

- TELL US ABOUT YOUR BUSINESS

MYSTIC FORMS is a handcrafted jewelry collection by a London-based Japanese artist Akiko Ban, co-directed with a graphic designer Taiyo Nagano.

Akiko is a practicing artist known for her lively drawings and sculptures that seek to establish a primitive, naturalistic and spiritual view of the world. In the process of creating this ‘Wearable Art’, she aims to create a special ritualistic and theatrical art object that acts as a prop and converts the wearer into an art piece themselves.

Akiko holds an MFA in Sculpture from Slade School of Fine Art and a BA in Drawing from Camberwell College. Her works have been exhibited internationally and her recent projects include the collaboration with Basement Jaxx and the high-end Japanese brand ‘matohu’. Her drawing was selected for RA summer show 2016.

- WHAT PART OF BEING A DESIGNER DO YOU PREFER? THE CREATIVE, SALES, SOCIAL OR MARKETING SIDE?

Of course, the creative as I’m an artist! I also enjoy talking with customers and get the direct feedback from them.

- WHAT IDEAS DID YOU TAKE ACTION ON/STEPS YOU TOOK TO GET YOUR BUSINESS UP AND RUNNING?

MYSTIC FORMS started as part of my artistic research project which explores the relationship between art and body. I have chosen jewelry as my medium to demonstrate my belief that art should be more accessible, personal and enjoyable for everyone. I am interested in how people’s perception of themselves changes by wearing my mystic artworks.

- WHAT HAS BEEN THE MOST EFFECTIVE WAY OF BUILDING YOUR TRIBE FOR YOUR BUSINESS AND GETTING NEW CUSTOMERS?

I would say being active on social media and stay connected with your followers and customers. Taking part in trade shows also helped me a lot to get exposure.

- WHAT HAVE BEEN YOUR BIGGEST CHALLENGES SO FAR?

Managing cash flow is always challenging.

Pre-existing creative based websites

Women who

- creative network for women

- events

- newsletter

- shop

- podcast

The Dots

- people

- companies

- hiring

Creative women's network

- thread projects

- support

- services

Inspiring creative women

- Free material-guides to Instagramb etc

- Blog

- Facebook community

- 'inspiring women of the month'

Feedback session

Concept one

An app design in which is a creative portal for women, outlining events, jobs and inspiring female ceo's etc.

Concept two

A website design in which is a creative portal for women, outlining events, jobs and inspiring female ceo's etc.

Question asked by myself...

- which do you prefer?

- what components should be added?

- do you think this would be an effective platform?

Feedback

- Could always complete both?

- if people will be uploading a cv a website is better.

- when you're in the mindsight of applying for jobs you do that sit down, in a professional environment at a computer

- Desktop-larger perspective-especially with design work-future employer can see your work more effectively

- portfolio surgeries

Survey__interface or print

20 participants from university (10:10-male:female)

How often do you read a magazine?

How often do you use an app?

How often do you read an article online?

How many apps do you have on your phone?

Do you prefer apps or websites?

How often do you read a magazine?

- It was found that the vast majority read 0-5 magazines per week

How often do you use an app?

- The majority of users use an app more than 17 times per day (further resarch may be conducted in order to gain a better idea of how many times apps are used per day)

How often do you read an article online?

- The majority say they read 0-5 articles a day

How many apps do you have on your phone?

- the majority of people have 4-7 apps on there phones

Do you prefer apps or websites?

- the selected outcome for this question was 'unsure'

Thoughts...

- Millenials interact more with digital content than print (on a daily basis)

- The average person has 4-7 apps on there phone

In conjunction to this information, it is evident that a user interface may be the most effective way in which to connect with millennials.

Daily userinferaces

In order to gather a greater understanding upon how important user interfaces are, a mindmap was conducted in order to record the user faces I used within one day.

From this it is evident that a range of mediums have been used in order to project this information, not just apps and websites. This is a factor in which I must consider when developing ideas.

Facebook

Instagram

-look at learning outcomes

-read studio briefs

From this it is evident that a range of mediums have been used in order to project this information, not just apps and websites. This is a factor in which I must consider when developing ideas.

The reasons in which I use some of these interfaces are listed below:

-keep in contact with friends

-watch videos

-store pictures

-messenger

Banking app

-Check balance

-easier than visiting an atm

-budgeting

-connect to other designers

-upload pictures

-keep a catalogue of images

-display work

Estudio

-view timetable-look at learning outcomes

-read studio briefs

Iplayer

-catch up with tv

-no actual tv so only form of watching

-to relax

From the information expressed it is clear that user interfaces have been used in order to develop a form of ease to the consumer. They are often short cuts to much more prolonged tasks, ie walking to an atm and checking your bank balance. Apps such as Iplayer allow the audience to consume relevant information in which they choose, a factor in which is highly influential within a younger audience.

Paper or pixel? Environmental impact

Paper or pixel?

Paper has gotten a bad rap in recent years. Detractors claim paper manufacturing leads to mass deforestation and contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. While paper supply chains could certainly use an overhaul, some of the arguments against using paper are just plain wrong.

"What people often don't realize is that the paper-making process is sustainable, and claims to the contrary are misleading to the consumer," said Mark Pitts , executive director of printing-writing, at the American Forest And Paper Association (AFANDPA).

Advertisement

According to the organisation, more than 65% of paper in the US was recycled in 2012, making paper the nation's most recyclable commodity. Over the past century, forest coverage in the northern part of the country, from Minnesota to Maine, has actually increased by 28% according to the United States Department of Agriculture's Forest Service.

On the surface, digital media does appear more sustainable. Electronic products such as phones and laptops are used over an over again, making it a renewable resource of sorts. But manufacturing electronic products also leaves a carbon footprint, as well as the energy needed to power them. And a growing concern is the rapid growth of discarded electronics, especially in developing countries.

E-waste is on the rise, with a global increase of 40m tons per year, especially in third world countries like India and South Africa, according to a 2009 United Nations report.

A lack of concrete information

For companies to assert that paperless is better for the environment, research is needed to back these claims, but there isn't much literature available comparing paper and e-media. One of the main reasons for this is that the two commodities are so different, and one has been around for far longer than the other.

As one of the oldest forms of communication, paper's life-cycle is easy to track, while e-media is young in relative terms. Companies must prove that they've looked at both and found electronics have a lower impact, Riebel said.

"We have to be careful when we pin one product against the other and say it's better. It's a tricky thing to do if you don't have all the data to back it up."

Paper comes in a variety of forms from many different manufacturers, so there will likely be a number of impacts, not just one that can be generally applied, said Arpad Horvath, a professor of engineering at the University of California-Berkeley.

Advertisement

More research is needed regarding the footprint of electronics, which means there is no "average environmental footprint" for e-media either, added Horvath, who, in 2004, published a study on the environmental impact of wireless technologies.

Conclusion

From the information researched it is clear that both digital and print based design can be bad for the environment.When thinking about a phone's 'shelf' life it is evident that apple products are often 'made to break' with the phones slowly dying over the two year contract period. This being very similar to the first ever lightbulb in which did not break. (In other words complying to the consumerist society in which we live).

Feedback session

After discussing the outcome with peers, they suggested that I alter the final outcome, developing a platform (UX) design in which allows creative women to engage with one another, forming inspiration and collaborations. They even suggested an online magazine (as younger audiences now consume their media online).

A further discussion was made surrounding whether the final outcome should be formatted as a website or app. There was a 50/50 split on this and therefore further research must be undergone.

A further discussion was made surrounding whether the final outcome should be formatted as a website or app. There was a 50/50 split on this and therefore further research must be undergone.

Sunday, 22 April 2018

Primary research: survey_women in the creative industry

In order to ensure young creative women have inspiration, a range of concepts were devised in which could act as platforms of influence.

Which concept do you prefer?

Concept one-

A small publication in which highlights creative women, using them as key inspiration.

Concept two-

An app in which allows creative women to connect with one another virtually, allowing for collaborations etc.

Concept three-

A collective, advertised with design collateral

Results

Primary research: Interview with Eve Warren

- Have you ever felt that being a women has limited your job opportunities within the creative industry? If so, how?

No never. I don't think it's a very healthy mindset to think your gender will effect your chances of gaining an opportunity in the creative industry. It's also wrong for an employer to employ and curate creative teams based on gender, race and ethnicity. I completely understand that as a women it can be a really daunting experience to walk into a studio full of men for an interview but in my experience all studios I've interacted with have all been keen to close their gender gap. I've always felt welcome and during my time at Fieldwork we were a very evenly split studio in terms of gender. Rather alarmingly though I've never worked in a studio where there have been people of colour. I do however work with someone who is deaf which is a first for me as I've rarely come across any designers with serious disabilities.

How do you feel design in the north compares to design in the south?

-What made you stay up north?

-How do you feel the transition between university and industry has been? and is there anything you regret not doing in uni?

No never. I don't think it's a very healthy mindset to think your gender will effect your chances of gaining an opportunity in the creative industry. It's also wrong for an employer to employ and curate creative teams based on gender, race and ethnicity. I completely understand that as a women it can be a really daunting experience to walk into a studio full of men for an interview but in my experience all studios I've interacted with have all been keen to close their gender gap. I've always felt welcome and during my time at Fieldwork we were a very evenly split studio in terms of gender. Rather alarmingly though I've never worked in a studio where there have been people of colour. I do however work with someone who is deaf which is a first for me as I've rarely come across any designers with serious disabilities.

To answer your question though I think freelancing in London, Manchester and Leeds has given me a great insight to how the North compares with the South. There's no doubt about it London pretty much has it all. There's a lot of heritage down here and for a long time London led the way in design on a global scale. However the North has some amazing stuff going on and it really bugs me that for a long time London has been a talent sucker but this is changing and I'm quite passionate to be part of that change.

When I first graduated I remember being quite petrified / obsessively concerned about what was going to happen at the end of my third year as my parents lived in rural Lincolnshire and I didn't see going home as an option. I also wasn't in any financial position to take sabbatical and go travelling for a few months or move to London. My boyfriend Martin is one half of Hungry Sandwich Club and was offered the free incubator space at Duke Studios, also at the time we signed for a flat with some left over grant money. It was all very frightening but the fact that we were able to sign for a affordable flat and work for free in a coworking space was amazing. This would never happen in London.

In hindsight I had a very smooth transition from university but only because I was organised. I think it's important to keep up some momentum and attempt to get a placement straight away. I won a placement at Manchester based design studio Fieldwork and worked there for a couple of months before interning at Golden. I really enjoyed my summer at Fieldwork and was fortunate that they wanted me back which eventually led to them offering me a full time position.

Most often graduates have no client or project management experience therefore you enter the industry at the bottom of the hierarchy. You go from being in total control of a university project to learning how to follow someone else's lead and vision. The transition can be quite difficult at times as many art degrees don't teach their students how to be commercially minded. This isn't a bad thing as there is always room for great ideas, it's just learning how to sell and execute them.

I think I regret not delving deeper into design theory...there's a lot of books I should have read. I also regret not pushing the idea of doing an exchange of some sort. It would have been great to study abroad.

COP 3 relevant quotes

Women in graphic Design 1890-2012 Frauen Und Grefik-Design (Gerda Breuer, Julia Meer (ED./HG.)

'For many reasons, which are also linked to historical processes, women are only marginally represented in the field of graphic design.

‘During the last quarter of the twentieth century, women played a central role in building the discourse of graphic design. During this period, the profession came of age both as a recognized business and as a field of study in university art and design programmes, including at the graduate level. Women were no minority among the educators, critics, editors, and curators who defined the theoretical issues of the time. Schools and museums provided accessible platforms from which women could influence the direction of graphic design.’

Key concepts in Feminist Theory and Research- Christina Hughes-SAGE Publications-2002

(33) ‘In the UK it is just over three decades ago that the Equal Pay Act (1970) was passed and over a quarter of a century ago that the Sex Discrimination Act (1975) was passed. Despite these changes, parity with men in all of these arenas is yet to be achieved. And, internationally, it should be remembered that such a legislation is not a global phenomenon.’

For example, the assumption that equality means ‘the same’ has been explored in terms of its political and philosophical implications. The notion that women should view the masculine as the normative, that is as the goal to be achieved, is certainly not one that is ascribed to all feminists’.

‘Graphic design history has largely foregrounded the achievements of male graphic designers, leaving the contribution of female graphic designers under-examined.’

(08/10/17)-https://www.designhistorysociety.org/blog/view/feature-where-are-the-women-gender-disparities-in-graphic-design-history

Quotes from 2nd year essay

‘This connection between “woman” and “artist” was neither biological nor metaphysical, but rather the historical product of how women established a presence in the visual arts’(Prieto, 2001)

‘few women were ever included in any museum shows; and women were seldom mentioned-except as models, muses, patrons, lovers and wives’ (Cottingham, 2000)

‘if you got any place as a woman you must be better than most women because everybody knew that women were inferior. You couldn’t identify with other women; the art world bore it out.’(Cottingham, 2000)

“Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? Less than 4% of the artists in the modern art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female”

When discussing the role of feminism within design culture, it is important to note key events in which occurred within the art world. As it may be suggested that design is a variation of art, with art focusing upon the expression of human creative skills, and design being developed “for a specific function” (Merriam-Webster, 2017)

In 2008, just 3.6% of the world’s creative directors were female.’ (Hanan, 2016)

‘few women were ever included in any museum shows; and women were seldom mentioned-except as models, muses, patrons, lovers and wives’ (Cottingham, 2000)

‘if you got any place as a woman you must be better than most women because everybody knew that women were inferior. You couldn’t identify with other women; the art world bore it out.’(Cottingham, 2000)

“Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? Less than 4% of the artists in the modern art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female”

When discussing the role of feminism within design culture, it is important to note key events in which occurred within the art world. As it may be suggested that design is a variation of art, with art focusing upon the expression of human creative skills, and design being developed “for a specific function” (Merriam-Webster, 2017)

In 2008, just 3.6% of the world’s creative directors were female.’ (Hanan, 2016)

The design council

According to ‘The Design Economy’ (our study published in 2015 highlighting the makeup of the UK design industry), we found that the design workforce was made up by a 78:22 gender split (men versus women), whereas the wider workforce we analysed had a 53:47 gender split in favour of men versus women.

The majority of design students are women – so where do they go?

Preparing for a talk at Ravensbourne on the history of women in design, I was dismayed to discover that work from female designers only accounts for 30% of the design curriculum at London’s Central Saint Martins (yet 70% of its students are women). The Guardian also reports that art and design degree courses in general are dominated by women. Yet a Design Council survey shows that only 40% of professional designers are female.

The thing is, they were there: the Nike swoosh; the original A-Z (look up Phyllis Pearsall – her story is amazing); the UK’s road signs; and the 1984 LA Olympic Games identity – they just never had the profile.

Without turning this into an essay about the evolution of the design industry, the industry we know and love today has some roots in the arts and crafts movement, where women were not only present, they were actively encouraged to embrace it as a “wholesome” pursuit. But, being as things were at the turn of the century, they were not allowed to hold any official memberships. Their “supporting role” was ingrained from the outset.

Moments in our feminist history, such as poster creation for the women’s Suffrage movement in the early 1900s, gave women designers their first foray into full creative control. Then, of course, war, and the world of work for women changed forever. We had kept the country going, and we were NOT going back. Introduction of the pill in the 1950s boosted our pay equality by 30%. Then we campaigned and got the Equal Pay Act in 1970 (granted, that has been in place for 47 years and women are still 18% behind – but that is a matter for a whole other editorial column).

Only 11% of design business leaders are women

So, here we are in 2017, political, biological and economic barriers have been gradually trampled down and, much like the good old arts and crafts days, we have no trouble attracting women to our industry. And yet, we still can’t seem to get more than 11% of them to the forefront.

So why don’t we get profile? Well, if you haven’t read Lean In by Sheryl Sandberg, then buy it now. Its mantra of “We’re holding ourselves back by not raising our hands, and by pulling back when we should be leaning in” is an important truth and I have yet to find a woman who has not identified with it at some point. Combined with this, women are less likely to build their networks or take platforms to speak, and we tell ourselves “how lucky we are” and continuously settle for what’s on offer rather than push and negotiate. I’ve done all of these things in my career.

Thankfully I found excellent role models, mentors and sponsors, who believed in me and pushed me to do more, and who still do. And I now have my own mentees, who constantly teach me in reverse.

The majority of design students are women – so where do they go?

Preparing for a talk at Ravensbourne on the history of women in design, I was dismayed to discover that work from female designers only accounts for 30% of the design curriculum at London’s Central Saint Martins (yet 70% of its students are women). The Guardian also reports that art and design degree courses in general are dominated by women. Yet a Design Council survey shows that only 40% of professional designers are female.

The thing is, they were there: the Nike swoosh; the original A-Z (look up Phyllis Pearsall – her story is amazing); the UK’s road signs; and the 1984 LA Olympic Games identity – they just never had the profile.

Without turning this into an essay about the evolution of the design industry, the industry we know and love today has some roots in the arts and crafts movement, where women were not only present, they were actively encouraged to embrace it as a “wholesome” pursuit. But, being as things were at the turn of the century, they were not allowed to hold any official memberships. Their “supporting role” was ingrained from the outset.

Moments in our feminist history, such as poster creation for the women’s Suffrage movement in the early 1900s, gave women designers their first foray into full creative control. Then, of course, war, and the world of work for women changed forever. We had kept the country going, and we were NOT going back. Introduction of the pill in the 1950s boosted our pay equality by 30%. Then we campaigned and got the Equal Pay Act in 1970 (granted, that has been in place for 47 years and women are still 18% behind – but that is a matter for a whole other editorial column).

Only 11% of design business leaders are women

So, here we are in 2017, political, biological and economic barriers have been gradually trampled down and, much like the good old arts and crafts days, we have no trouble attracting women to our industry. And yet, we still can’t seem to get more than 11% of them to the forefront.

So why don’t we get profile? Well, if you haven’t read Lean In by Sheryl Sandberg, then buy it now. Its mantra of “We’re holding ourselves back by not raising our hands, and by pulling back when we should be leaning in” is an important truth and I have yet to find a woman who has not identified with it at some point. Combined with this, women are less likely to build their networks or take platforms to speak, and we tell ourselves “how lucky we are” and continuously settle for what’s on offer rather than push and negotiate. I’ve done all of these things in my career.

Thankfully I found excellent role models, mentors and sponsors, who believed in me and pushed me to do more, and who still do. And I now have my own mentees, who constantly teach me in reverse.

Rebecca Wright on the ratio of girls with design degrees vs. those in the industry

We often find ourselves discussing the role, and lack of women in the world of graphic design. Rather than try and cackhandedly work it out for ourselves we decided to ask someone at the frontline of the issue to help explain it. Rebecca Wright is programme director of graphic communication design at Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. With Lucienne Roberts, she is also co-founder of GraphicDesign&, a pioneering publishing house exploring the relationship between graphic design and the wider world, and the value that it brings. GraphicDesign& will be launching a survey for graphic designers in early 2015 as part of a new project which uses social science to look at who graphic designers are and how they work.

Here she is on the enormous amount of girls who study design degrees, compared with the very small few that go on to become big names in the industry. As ever, feel free to leave your comments below.

There’s a funny thing going on with graphic design and girls. It’s noticeable on HE courses up and down the country and writ large as the new academic year begins again. For of all the students arriving and returning to study undergraduate and postgraduate graphic design, the majority are female.

“A 2013 Guardian survey reports that of the 12,930 students at the University of the Arts London, of which CSM is part, 9,370 are female – a pretty weighty 72.5%”

Rebecca Wright

At Central Saint Martins this is by no slight margin. Of the 525 students enrolled this year on BA Graphic Design, 372 are female, which is 70.8%. The picture is similar on MA Communication Design where female students are 68.3% of the cohort. Within the broader context of art and design education, this is not in itself unusual. A 2013 Guardian survey reports that of the 12930 students at the University of the Arts London, of which CSM is part, 9370 are female – a pretty weighty 72.5%. And of the 49,920 students studying creative arts and design in Higher Education in the UK, 30,790 or 61.7%, are women. What is unusual however, and deserves scrutiny, is that this female domination in graphic design education appears to be reversed when it comes to the graphic design industry.

“This female domination in graphic design education appears to be reversed when it comes to the graphic design industry.”

Rebecca Wright

A much-quoted survey of the UK design industry published by the Design Council in 2010 revealed that only 40% of designers were women, in startling contrast to the 70% of female design students. This statistic prompted dissertations and magazine articles, questions to awards panels and industry line-ups, and both defence and dispute. And yet, despite the debate, there are areas of the industry where there seems little evidence of significant change.

Attend any design conference and the likelihood is still that the speakers will be predominantly male; look at the boards, panels, juries, the partners, chairpersons and even the majority of awards winners, and the picture is the same. Because, although in rank and file the number of women in graphic design is surely growing, it’s in the high profile positions and public platforms where the gender imbalance remains most visible.

“Attend any design conference and the likelihood is still that the speakers will be predominantly male; look at the boards, panels, juries, the partners, chairpersons and even the majority of awards winners, and the picture is the same.”

Rebecca Wright

And this is a problem. It’s a problem because, as in many other walks of life, the higher echelons of the industry does not reflect the demographic it purports to represent; neither the future of the industry nor the audience it serves. Yet there was a never a time when we needed this more. Unprecedented social, economic and health related challenges necessitate 360 degree thinking: a diverse range of people and perspectives to innovate, propose and provide. While graphic design education strives to provide an environment of equality and pluralism where competition thrives and meritocracy is the measure, there is a culture in parts of the industry that lags behind – it may recognise the value of talent and graft, but it rewards confidence, charisma and chutzpah, and the uncomfortable truth is that these attributes do not always sit as comfortably with women as they often do with men.

“After 15+ years in design education, my experience is that female students are still less likely to want to grab the limelight, less inclined to push themselves forward and to self promote.”

Rebecca Wright

This is not to suggest that to be a woman has a bearing on levels of skill and competency in the discipline – great graphic design is created by both male and female students, and in this regard the issue of gender is of little concern. However, after 15+ years in design education, my experience is that female students are still less likely to want to grab the limelight, less inclined to push themselves forward and to self promote. These students show their confidence in other ways – in the events they organise, coordinate and manage, the group work they often lead and the imagination and innovation with which they develop their project work. But the lack of fanfare that accompanies these activities may lie behind the lack of visibility of women graphic designers at those top tables.

“Few courses explicitly discuss the issue of gender in the contemporary graphic design industry, or the hierarchical structures and cultural machismo that persist.”

Rebecca Wright

The best graphic design courses teach their students, regardless of gender, to be skilful, articulate and agile designers: to empathise, to work with and not just for their clients and end-users, to take their role as citizens seriously. These courses create the space for young designers to flex their creative muscle, take risks, push boundaries and make mistakes, to think freely and act consciously. I’m not suggesting any of this should change. But maybe we should be more honest about where resistance and potential inequalities lie. Few courses explicitly discuss the issue of gender in the contemporary graphic design industry, or the hierarchical structures and cultural machismo that persist. But if we want to equip our students to have influence in industry, and for its shape and face to change, perhaps it is time that more of us did so.

Throughout the month of October we’ll be celebrating the well-known autumnal feeling of Back to School. The content this month will be focusing on fresh starts, education, learning tools and the state of art school in the world today – delivered to you via fantastic in-depth interviews, features and conversations with talented, relevant, creative people.

Survey

In order to gain a better understanding of how women themselves feel of the creative industries pay gap, a survey was conducted. Survey monkey was selected as the service to establish this, as it has strong shareable links.

Questions asked:

Are you a female?

What female creatives inspire you?

Are these creatives based in Leeds?

Do you think there is a lack of publicised female creatives?

Are you aware of the gender pay gap within the creative industry?

Do you believe there are more famous creative males than females?

Results...

30 participants took part in the survey, with the results as following:

_________________________________________________________________________________

Are you a female?

Yes-20

No-10

_________________________________________________________________________________

What female creatives inspire you?

A range of creatives were listed, with the most common results appearing included Jessica Walsh, Kate Moross, and Paula Scher.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Are these creatives based in Leeds?

The fast majority responded no to this question, although names such as Eve Warren and Louise Lockhart were outlined.

No-27

Yes & comment-3

_________________________________________________________________________________

Questions asked:

Are you a female?

What female creatives inspire you?

Are these creatives based in Leeds?

Do you think there is a lack of publicised female creatives?

Are you aware of the gender pay gap within the creative industry?

Do you believe there are more famous creative males than females?

Results...

30 participants took part in the survey, with the results as following:

_________________________________________________________________________________

Are you a female?

Yes-20

No-10

_________________________________________________________________________________

What female creatives inspire you?

A range of creatives were listed, with the most common results appearing included Jessica Walsh, Kate Moross, and Paula Scher.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Are these creatives based in Leeds?

The fast majority responded no to this question, although names such as Eve Warren and Louise Lockhart were outlined.

No-27

Yes & comment-3

_________________________________________________________________________________

Do you think there is a lack of publicised female creatives?

Yes-20

No-6

Unsure-4

Strongest responses:

I think that it is improving but certainly in the past.

yes!! all the female creatives I know are due to me researching them! there's hardly any exposure for female creatives

yes, although I know some female creatives from uni I feel that there is a real lack of women represented within the design industry.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Are you aware of the gender pay gap within the creative industry?

Yes-7

No-10

Partly-6

Unsure -7

_________________________________________________________________________________

Do you believe there are more famous creative males than females?

Yes-22

No-5

Unsure-3

Conclusion

From the information gathered it is evident that there is a lack of knowledge surrounding the gender pay gap within graphic design, as well as 'famous' female graphic designers.

Saturday, 21 April 2018

Female freelancers being paid less

£4,000 difference

Gender-based wage discrimination in traditional business settings can be insidious because women who start out being paid less may be continuously offered less competitive raises or salaries when they change jobs. But many female entrepreneurs in creative fields—perhaps even those who think that owning their own business shelters from such bias—are actually seeing a similar disparity play out in a different way.

These women still have to set their job rates or negotiate project fees, and many feel that they’re treated differently and afforded less bargaining power than men. As a result, the pay gap among self-employed female creatives is actually far worse. And many may not even be aware of it.

Lack of female role models? specifically in design

Sarah Weir (OBE), chief executive, design council

“Today, the greatest issues facing female designers are a lack of pay and the lack of having their voices heard. 100 years ago, some women were given a voice through having the vote. However, only 50 years ago, an advert in a design magazine appeared calling for a man between the ages of 30-40 to fulfill an important job opportunity as an art director.

Conversely, in 2015, 78% of the design economy was male, compared to 53% across the whole working economy. The gender pay gap is very much alive and well today! Our own 2015 research noted the average salary was £635 per week, with the majority of women earning a whopping 68% less. We need to do better!

The answer is to provide more platforms to hear women in different areas of design and pay them equally with men.”

“One of the biggest challenges we face is lack of women in visible leadership positions — the majority of design graduates are women, but only 11% of design business leaders are women. The idea of ‘You can’t be what you can’t see’ could play a big part in changing that. In the past, female designers haven’t had the same profile as their male counterparts (just google ‘famous graphic designers’ to see what that looks like) and we’re at the point where we can really change that. It’s important for leading female designers to put themselves at the forefront — be vocal about their work, volunteer to give talks, get on judging panels and generally be seen in the industry. Of course it’s not only women that can help address this, men have a role too — to help women get the opportunities, platforms and support needed for them to flourish and be seen.”

“There is a lack of role models – visibility of female designers above design director level is lacking. If you’re female and happen to be in an imbalanced workplace, it can feel like a boy’s club. You do begin to wonder, what will happen to my career when and if I reach that level? Where have all the women gone? I’m sure it’s not just a childcare issue. There’s a problem with investing confidence in women at leadership levels. Employers need to make sure we’re seeing women at the top. Equality is not just a female problem, it’s an industry problem.”

“Today, the greatest issues facing female designers are a lack of pay and the lack of having their voices heard. 100 years ago, some women were given a voice through having the vote. However, only 50 years ago, an advert in a design magazine appeared calling for a man between the ages of 30-40 to fulfill an important job opportunity as an art director.

Conversely, in 2015, 78% of the design economy was male, compared to 53% across the whole working economy. The gender pay gap is very much alive and well today! Our own 2015 research noted the average salary was £635 per week, with the majority of women earning a whopping 68% less. We need to do better!

The answer is to provide more platforms to hear women in different areas of design and pay them equally with men.”

Tessa Simpson, design director, O Street

Jane Harwood, senior designer, Williams Murray Hamm

Honeybook’s 2017 Gender Pay Gap Creative Economy Report

According to Honeybook’s 2017 Gender Pay Gap Creative Economy Report, women make 32 percent less than men in creative industries, like writing, graphic design, and videography.

Take a moment to let that sink in.

Now, let me make you feel worse. On average, across all industries, women make 24 percent less than men. In the financial service industry, the pay gap rises to approximately 30 percent. Other fields, such as public administration, science and tech, trail right behind. All of these fields are dominated most often by traditionally employed professionals. When someone works a nine to five, her salary is largely dictated by her managers and the HR department. Her salary is slightly out of her hands.

However, so many creatives are part of the gig economy, which makes up 36 percent of the US workforce. We work alone. We’re our own bosses. We decide the trajectory of our careers—which means we get to set our own rates.

So where’s the disparity?

Why are the female photographers, writers, and other creatives getting paid 32 percent less than their male counterparts, despite, according to Honeybook, “80 percent having college and graduate degrees and performing similar work”?

_________________________________________________________________________________

The reality is...

Of these diverse businesses, HoneyBook was able to drill down on certain industries, and found that the pay gap varies greatly amongst different professions. In some cases, the gap becomes more staggering. In others, it’s less pronounced — but still far from balanced.

Over 37% of female creative entrepreneurs are making less than $9 per hour. Despite the fact that 73% of creative entrepreneurs, both male and female, hold bachelor's degrees, over a third of the female creative entrepreneurs still make less than the minimum wage in 15 states.

Of these diverse businesses, HoneyBook was able to drill down on certain industries, and found that the pay gap varies greatly amongst different professions. In some cases, the gap becomes more staggering. In others, it’s less pronounced — but still far from balanced.

Women are disproportionately earning lower hourly wages.

37% of female creatives are earning $9 per hour or less in revenue compared to only 20% of male creatives.

24% of female creatives are earning $5 per hour or less in revenue compared to only 11% of male creatives.

While men are disproportionately earning higher hourly wages.

Only 7% of female creatives are earning over $50 per hour in revenue compared to 19% of male creatives.

Only 25% of female creatives are earning over $25 per hour in revenue compared to 45% of male creatives.

61% pointed to negotiating power, meaning that women are less likely to negotiate higher costs and are treated differently during negotiations.

47% pointed to wage secrecy, meaning that women are underpaid without knowing it.

40% pointed to The “Motherhood Penalty,” which is the opportunity cost of being a mother and perceived lower commitment.

Equality and Human Rights Commission Research report 109

Malcolm Brynin Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex

Gender role theory

Differential gender roles are adopted early on in life and influence much of what happens in the home, school, personal relationships, family life and employment (see, for example: Lips, 2012; Ochsenfeld, 2014; Rubery, 2008). Therefore men and women often follow different paths in education and employment, which lead to overall differences in pay. Segregation into traditional gender roles is often not a conscious 'choice' for either women or men. Rather, these choices are constrained by social pressures and expectations, and are passed on from one generation to the next.

Occupational segregation

Occupations that have high proportions of women working in them are often referred to as 'feminised'. It has been found that the higher the proportion of women who work in an occupation the lower the average pay within it (Blau and Kahn, 2003; Bettio and Verashchagina, 2009; Levanon et al., 2009). Both men and women within feminised occupations experience lower pay, although because women obviously outnumber men they are disproportionately affected.

In the UK, Olsen et al. (2010) attribute 17% of the pay gap to occupational segregation by gender. Other research on the combined effects of occupational segregation and segregation within the workplace (that is, men and women performing different roles in the same workplace) finds a larger gap (Mumford and Smith, 2009), though in this case segregation is more important for the part-time than for the full-time gender pay gap.

Segregation, however, is difficult to analyse because of different datasets and definitions, while its effects are difficult to interpret because segregation is the result of both supply (men and women tending to gravitate to different types of jobs) and demand (for example, employers’ prejudices may act as a barrier). Explanations for occupational segregation often include the gender role argument described above, but other factors might include family constraints that, for instance, encourage entry into part-time work, which mostly occurs in more routine occupations.

It is also unclear why average pay is lower in more feminised occupations. It might be that women are paid less (for whatever reason), and that when they segregate into specific occupations, average wages in these must by definition be lower. However, both men and women who work in feminised occupations are paid less on average than those in non-feminised ones. It is possible of course that family and social pressures cause women to enter into low-paid occupations as a second-best option. This would mean more women than men ending up in low-paid occupations and could help explain why feminised occupations tend not to pay well.

Insofar as segregation is a problem, desegregation would seem to be the answer. However, research in the United States found that the effect of desegregation on equality is complex and inconclusive (Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey, 2012). Further evidence from the US shows that occupational gender segregation is in decline (Hegewisch et al., 2010; Olsen et al., 2010, b; American Association of University Women, 2012), as is the gender pay gap, but the relationship between the two may also be weakening (Charles and Grusky, 2004). The effects of segregation are not consistently negative for women. Highly skilled women, for example, are sometimes very well paid in highly feminised occupations. This would mainly seem to be the result of women entering highly professionalised public sector work, often at management level, for instance in social work (Esping-Andersen, 1993; Brynin and Perales, 2016).

Finally, inequality arises partly through ‘vertical segregation’, that is, men occupying higher positions within an occupation, and partly through ‘horizontal segregation’ (in other words occupational segregation) men and women working in different occupations). Horizontal segregation suggests that women's work is often undervalued (see 3.1.4 below). Vertical segregation highlights the problem of the ‘glass ceiling’ as a barrier to women reaching senior positions.

Whatever the exact cause of occupational segregation, it is clear that women tend to be over-represented in the following low-paid jobs (the ‘five Cs’): cleaner, caterer, carer, cashier, and clerical worker (Joint Negotiating Committee for Higher Education Staff (JNCHES), 2011; Grimshaw and Rubery, 2007). This concentration of women in jobs which do not require significant, if any, qualifications, and which are often part-time, lowers women’s average pay relative to men’s.

Undervaluation theory

The persistence of the gender pay gap suggests the possibility of a stigma associated with occupational feminisation – that work done by women is socially and economically undervalued. This theory is most prevalent in the United States (see, for example: England, 1992, 2005, 2010) though it is also supported in the UK (for example Perales, 2013). The theory posits that society undervalues certain types of work precisely because women do it.

Pay practices are ‘socially constructed’ and lead to undervaluation of women’s labour in a range of ways – pay is heavily influenced by social pressures and norms, as well as by the actions of employers, governments and trade unions. Pay is often decided based on typically male behaviours such as performing long hours, working continuously for a long time and an aggressive negotiating style. By not conforming to these norms, some women lose out. On the other hand, women are still seen by society as secondary earners, as well as likely to derive more intrinsic reward from their work than men, thereby justifying lower salaries (Grimshaw and Rubery, 2007).

Given the overall trend towards a narrowing of the gender pay gap, however, it could be that undervaluation theory is becoming less relevant (Jackson, 2008). The fact that the gender pay gap varies across different countries suggests devaluation is not universal or uniform (Bettio, 2002; Bettio and Verashchagina, 2009).

Further, many jobs in which women predominate are not stereotypically ‘feminine’ – for instance, clerical work (Hakim, 1998) – and gender-integrated occupations are generally better paid than both female-dominated and male-dominated occupations (Hakim, 1998; Cotter et al., 2004; Magnusson, 2013). It also seems to be the case that women have gained in wage terms from working in skilled occupations and that there is an underlying trend in productivity in favour of women who are benefitting from the shift to a skills-based, non-manual economy (Brynin and Perales, 2016). This also undermines the theory in general but it remains possible, Brynin and Perales argue, that the work of less qualified women is undervalued. In sum, proving the empirical validity of undervaluation (or devaluation) theory has not been easy. Insofar as the theory is correct, however, the solution is to assess the comparative worth of feminised against less feminised occupations.

Finally, the pursuit of parity in gender pay has proven to be highly complex and has been described as a ‘case of constantly moving goalposts’ (Rubery and Grimshaw, 2014). The authors argue that pay setting is linked with wider societal and economic trends, such as the growing disparity in wealth and the waning influence of trade unions. ‘Levelling down,’ whereby men’s pay is reduced by employers to the same level as women’s, may reduce gender pay inequality but polarise incomes as a whole. In this scenario, those on low and middle incomes experience wage stagnation while those on high incomes have much faster wage growth.

The size of the pay gap and trends

The differences between the pay of men and women in employment have been examined in detail in many countries for a number of years. A general consensus exists as to the size of the UK gender pay gap, the direction of travel and the main factors contributing to it.

The Annual Survey of Household Earnings (ASHE) is a key source of data on the gender pay gap. Its findings are based on a 1% sample of employee jobs taken from HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and Pay As You Earn (PAYE) records; it does not cover the self-employed. The median, full-time gender pay gap decreased from 9.6% in 2014 to 9.4% in April 2015. This is the lowest since the survey began in 1997, although the gap has not changed very much in recent years. Including part-time employees in the overall analysis, the pay gap in 2015 stood at 19.2%, the same as in 2014. Comparing the pay of part-time men with part-time women, women have a pay advantage of 6.5% in 2015, up from 5.5% the year before (ONS, 2015).

A previous Commission report (Perfect, 2013) found that, based on ASHE data, the median, full-time gender pay gap had fallen from 17% in 1997 to 10% in 2010.

An earlier Commission report (Metcalf, 2009) reviewed various studies based on different datasets covering the late 1990s to the early 2000s. These gave an unadjusted pay gap of around 20%-25%, but in one instance this was as low as 14% and in another as high as 42%. This raw pay gap is the simple difference between average male and female wages and does not therefore control for other factors. When controlling for factors such as the average education of men and women or the proportion in part-time work, the gap falls to around 10% in most cases. This residual gap could be due to discrimination but also arises out of unexplained factors (information not available in the data).

- According to the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, the median gender pay gap for full and part-time workers in 2016 was 18.1%. The gap for full-time employees only was smaller at 9.4%. While part-time women tended to earn slightly more than part-time men (6%), part-time women earned 36.5% less than full-time men. Women are much more likely to work part time than men.

- Based on the analysis of Labour Force Survey (LFS) data – the source for all of the analysis in this report - the mean gender pay gap has reduced considerably. As a percentage of male earnings, for full and part-time work, it fell from 27% in 1993 to 10% in 2014.

- The gender pay gap is a longstanding phenomenon and its causes are complex. Social pressures and norms influence gender roles and often shape the types of occupations and career paths which men and women follow, and therefore their level of pay. Women are also more likely than men to work part-time and to take time out from their careers for family reasons.

- The effect of ‘occupational segregation’ – the division of men and women into different occupations – on pay has lessened. However, within occupations, on average women are still paid less than men suggesting they are either being paid less for doing broadly the same work or they have lower level jobs in the same company

- Women not only earn less than men overall, they are more likely to be low paid. In 2014, 20.4% of men earned less than £8 per hour while 30.3% of women did so. However, the proportion of women experiencing low pay has declined over time.

- Nearly two-fifths of women in employment are part-time and four times as many women as men work part-time. Male and female part-time workers generally earn less per hour than full-time workers, but women who work part-time generally earn more than men who do so.

- The pay gap widens with age: older women experience a larger pay gap compared with their male peers than younger women with their male peers. This is primarily because women are more likely than men to take time out of the labour market to care for children. This may slow career development. The statistical analysis found that women's shorter job tenure, a likely consequence of starting a family, is a factor driving the pay gap.

- While younger married women earn more than unmarried women, this advantage reverses with age. From their 40s onwards, married women experience a pay disadvantage compared to unmarried women. This is likely to be linked with child-rearing: the analysis found that having a child increases the pay gap considerably for women. Married men, by contrast, earn substantially more than unmarried men in all age groups. The ‘wage penalty’ for child-rearing, as a proportion of women’s pay, has increased slightly over time. However, as with the gender pay gap generally, the pay gap between men and women with children has also declined over time.

- There appears to be a relationship between housework and the pay gap. Across the whole sample, women do more housework than men, and the demands of housework do not affect women and men in the same way. Where women work fewer hours they do more housework but men do not vary their housework hours relative to hours worked – their contribution tends to remain low regardless. Women that do the largest amounts of housework experience a pay gap even when compared with the small number of men who also do a lot of housework.

Gender role theory

Differential gender roles are adopted early on in life and influence much of what happens in the home, school, personal relationships, family life and employment (see, for example: Lips, 2012; Ochsenfeld, 2014; Rubery, 2008). Therefore men and women often follow different paths in education and employment, which lead to overall differences in pay. Segregation into traditional gender roles is often not a conscious 'choice' for either women or men. Rather, these choices are constrained by social pressures and expectations, and are passed on from one generation to the next.

Occupational segregation

Occupations that have high proportions of women working in them are often referred to as 'feminised'. It has been found that the higher the proportion of women who work in an occupation the lower the average pay within it (Blau and Kahn, 2003; Bettio and Verashchagina, 2009; Levanon et al., 2009). Both men and women within feminised occupations experience lower pay, although because women obviously outnumber men they are disproportionately affected.

In the UK, Olsen et al. (2010) attribute 17% of the pay gap to occupational segregation by gender. Other research on the combined effects of occupational segregation and segregation within the workplace (that is, men and women performing different roles in the same workplace) finds a larger gap (Mumford and Smith, 2009), though in this case segregation is more important for the part-time than for the full-time gender pay gap.

Segregation, however, is difficult to analyse because of different datasets and definitions, while its effects are difficult to interpret because segregation is the result of both supply (men and women tending to gravitate to different types of jobs) and demand (for example, employers’ prejudices may act as a barrier). Explanations for occupational segregation often include the gender role argument described above, but other factors might include family constraints that, for instance, encourage entry into part-time work, which mostly occurs in more routine occupations.

It is also unclear why average pay is lower in more feminised occupations. It might be that women are paid less (for whatever reason), and that when they segregate into specific occupations, average wages in these must by definition be lower. However, both men and women who work in feminised occupations are paid less on average than those in non-feminised ones. It is possible of course that family and social pressures cause women to enter into low-paid occupations as a second-best option. This would mean more women than men ending up in low-paid occupations and could help explain why feminised occupations tend not to pay well.

Insofar as segregation is a problem, desegregation would seem to be the answer. However, research in the United States found that the effect of desegregation on equality is complex and inconclusive (Stainback and Tomaskovic-Devey, 2012). Further evidence from the US shows that occupational gender segregation is in decline (Hegewisch et al., 2010; Olsen et al., 2010, b; American Association of University Women, 2012), as is the gender pay gap, but the relationship between the two may also be weakening (Charles and Grusky, 2004). The effects of segregation are not consistently negative for women. Highly skilled women, for example, are sometimes very well paid in highly feminised occupations. This would mainly seem to be the result of women entering highly professionalised public sector work, often at management level, for instance in social work (Esping-Andersen, 1993; Brynin and Perales, 2016).

Whatever the exact cause of occupational segregation, it is clear that women tend to be over-represented in the following low-paid jobs (the ‘five Cs’): cleaner, caterer, carer, cashier, and clerical worker (Joint Negotiating Committee for Higher Education Staff (JNCHES), 2011; Grimshaw and Rubery, 2007). This concentration of women in jobs which do not require significant, if any, qualifications, and which are often part-time, lowers women’s average pay relative to men’s.

Undervaluation theory

The persistence of the gender pay gap suggests the possibility of a stigma associated with occupational feminisation – that work done by women is socially and economically undervalued. This theory is most prevalent in the United States (see, for example: England, 1992, 2005, 2010) though it is also supported in the UK (for example Perales, 2013). The theory posits that society undervalues certain types of work precisely because women do it.

Pay practices are ‘socially constructed’ and lead to undervaluation of women’s labour in a range of ways – pay is heavily influenced by social pressures and norms, as well as by the actions of employers, governments and trade unions. Pay is often decided based on typically male behaviours such as performing long hours, working continuously for a long time and an aggressive negotiating style. By not conforming to these norms, some women lose out. On the other hand, women are still seen by society as secondary earners, as well as likely to derive more intrinsic reward from their work than men, thereby justifying lower salaries (Grimshaw and Rubery, 2007).

Given the overall trend towards a narrowing of the gender pay gap, however, it could be that undervaluation theory is becoming less relevant (Jackson, 2008). The fact that the gender pay gap varies across different countries suggests devaluation is not universal or uniform (Bettio, 2002; Bettio and Verashchagina, 2009).

Further, many jobs in which women predominate are not stereotypically ‘feminine’ – for instance, clerical work (Hakim, 1998) – and gender-integrated occupations are generally better paid than both female-dominated and male-dominated occupations (Hakim, 1998; Cotter et al., 2004; Magnusson, 2013). It also seems to be the case that women have gained in wage terms from working in skilled occupations and that there is an underlying trend in productivity in favour of women who are benefitting from the shift to a skills-based, non-manual economy (Brynin and Perales, 2016). This also undermines the theory in general but it remains possible, Brynin and Perales argue, that the work of less qualified women is undervalued. In sum, proving the empirical validity of undervaluation (or devaluation) theory has not been easy. Insofar as the theory is correct, however, the solution is to assess the comparative worth of feminised against less feminised occupations.

Finally, the pursuit of parity in gender pay has proven to be highly complex and has been described as a ‘case of constantly moving goalposts’ (Rubery and Grimshaw, 2014). The authors argue that pay setting is linked with wider societal and economic trends, such as the growing disparity in wealth and the waning influence of trade unions. ‘Levelling down,’ whereby men’s pay is reduced by employers to the same level as women’s, may reduce gender pay inequality but polarise incomes as a whole. In this scenario, those on low and middle incomes experience wage stagnation while those on high incomes have much faster wage growth.

Measuring and explaing the gender pay gap

The differences between the pay of men and women in employment have been examined in detail in many countries for a number of years. A general consensus exists as to the size of the UK gender pay gap, the direction of travel and the main factors contributing to it.

The Annual Survey of Household Earnings (ASHE) is a key source of data on the gender pay gap. Its findings are based on a 1% sample of employee jobs taken from HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and Pay As You Earn (PAYE) records; it does not cover the self-employed. The median, full-time gender pay gap decreased from 9.6% in 2014 to 9.4% in April 2015. This is the lowest since the survey began in 1997, although the gap has not changed very much in recent years. Including part-time employees in the overall analysis, the pay gap in 2015 stood at 19.2%, the same as in 2014. Comparing the pay of part-time men with part-time women, women have a pay advantage of 6.5% in 2015, up from 5.5% the year before (ONS, 2015).

A previous Commission report (Perfect, 2013) found that, based on ASHE data, the median, full-time gender pay gap had fallen from 17% in 1997 to 10% in 2010.

An earlier Commission report (Metcalf, 2009) reviewed various studies based on different datasets covering the late 1990s to the early 2000s. These gave an unadjusted pay gap of around 20%-25%, but in one instance this was as low as 14% and in another as high as 42%. This raw pay gap is the simple difference between average male and female wages and does not therefore control for other factors. When controlling for factors such as the average education of men and women or the proportion in part-time work, the gap falls to around 10% in most cases. This residual gap could be due to discrimination but also arises out of unexplained factors (information not available in the data).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)